Committee History

Early Years

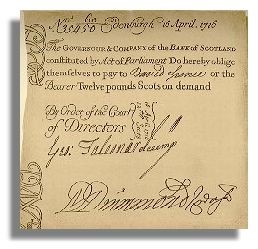

Bank of Scotland, founded by Act of The Scottish Parliament in 1695 and The Royal Bank of Scotland, formed by Royal Charter in 1727, showed no love for each other in their early years but, from 1750, when small private banks began to appear, the two "public" banks came together to protect their interests. The primary cause for concern was that of note issues. Practically all the private banks issued their own notes, often with scant security and with some form of option about repayment. The two established banks saw here not only a menace to their own development but an inflationary danger to the Scottish economy as well. Eventually, following an initiative by The Royal Bank, a "memorial" was prepared in 1764 concerning "The paper money used in Scotland" and soliciting "An Act of Parliament against the illegal banking companies in Scotland". Thus was formed a body comprising both banks to take joint action to solve a common problem. (Prior to this demonstration of support for each other, the banks had made strategic use of their own note issues to embarrass one another!).

The banks' joint action met with little success - the perception of the Lord Privy Seal being that: "The trade of banking is not a matter of public favour but of right to every subject". In light of this, and conscious of the necessity for economic stability (and mindful, no doubt, of their own interests), the two banks continued to meet together from time to time as occasion warranted with a view to ensuring that private banks should, at least, be subject to the same restraints in trade as themselves. Very broadly, these restraints had been imposed by Government following the impact of the failure of the Darien Scheme and other crises. Some of these measures affected note issuing activity and a measure of control, therefore, was already imposed on the two "public" banks which did not apply to private banks. The question of note issues was largely resolved, although not entirely to the satisfaction of the "old" banks, by a statute in 1765 which, broadly, brought all note issues onto the same footing - and further legislation on note issues was introduced in later years. But the thing that made the real difference was the establishment of a note exchange in the early 1770's. The two

19th Century Co-operation

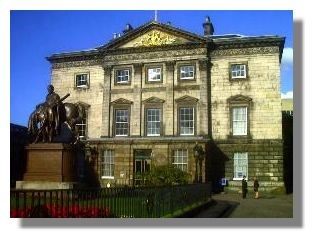

There is little of relevance to the history of the Committee (as yet un-named) in the latter years of the 18th Century but co-operation was further formalised in 1809 when Directors of both banks considered "the expediency of a mutual sederunt book .... the Secretary of the Bank of Scotland to keep the same." The allocation of this duty was probably responsible for the Bank's pre-eminence in future meetings. Interestingly, the Directors at this time also considered the banks' involvement in funding "improvements of the passage across the Firth of Forth called the Queensferry" - evidence of co-operation extending to other areas.

Later that year there is the first record of a meeting involving other banks when

Bank of Scotland and The Royal Bank were joined by Messrs Ramsay, Bonar

and Company and Sir William Forbes and Company to discuss, mainly, the remittance of revenue from the Board of Customs in Scotland to the Lords Commissioners of the Treasury. However, although co-operation and numbers were increasing not all new players were welcomed. This is evident from the considerable concern experienced by the original "two" over the emergence, in 1810, of "A new banking company projected at Edinburgh" under the nomination of the General Commercial Bank of Scotland with, as an inducement to subscribers that they shall not be universally liable for the obligations of the company but only to the extent of the sums immediately subscribed." (In effect, establishing the principle of limited liability in advance of company legislation in later years). Bank of Scotland, The Royal Bank and The British Linen Company (BL), by the nature of their statutes, already enjoyed this protection.

Again in 1810 the two banks sought to restrict the development of the "BL". However, by 1819, there were meetings involving the four banks mentioned at the beginning of the preceding paragraph plus The Commercial Banking Company and, by 1838, The British Linen and The National Bank of Scotland were also present at meetings. A year later the banks were further augmented, at least on occasion, by the new joint-stock banks, Western Bank, Clydesdale Bank and Edinburgh and Leith Bank.

Throughout this period of expansion there are no references to indicate the basis, terms, mechanics, or even permanency for inclusion of those "other" banks although, around this time, there is an isolated reference to a "Committee of Edinburgh Banks". The fact that such reference is isolated may imply that the breadth of the forum depended on the circumstances prevailing at the time. The banks, or some of them (but always dominated by Bank of Scotland and The Royal Bank) continued to meet frequently though randomly (2/3 times a month) and by the end of 1863 meetings regularly comprised: Bank of Scotland, The Royal Bank, The British Linen Company, Commercial Bank of Scotland, National Bank of Scotland, Union Bank of Scotland, Clydesdale Bank and City of Glasgow Bank.

Topics for discussion most commonly concerned the need to preserve stability in the economy. In their eyes this meant that the rate for discounting bills and interest rates had to be regulated. On one occasion, procedures for dealing with bills of exchange falling due on an Edinburgh Sacramental Fast Day were discussed. (They agreed that "The bank doors will be open, or say half open (!), at 9.00 am and closed for the day at 11.00 o'clock"). There are also references to cheque clearing and, in 1873, Bank of Scotland, The Royal Bank and The British Linen formed a group for the purpose of "Revising and reporting on the Edinburgh Clearing House Rules"; a year or so later the banks were refining the rules for the exchange and settlement of notes as well as the terms for conducting business with, and of, savings banks. The consideration given to cheque clearing and note exchanges, when viewed against such continuing operations today (albeit in different formats) set a solid base for the success of subsequent inter-bank operations and co-operation.

Agreements and Understandings

It is clear that the meetings now taking place had more to do with co-operation than competition; in earlier years meetings were referred to as "Meetings of both (or 'Edinburgh' or 'Scotch') Banks", or simply "Meetings of Banks". Now, however, they are regularly described as "Meetings of Bank Managers" - a manager, presumably, being the bank's most senior official (as distinct from local "agents"). Meetings were always convened, led by, and held in Bank of Scotland - probably stemming from their responsibility for the "Mutual Sederunt Book" mentioned earlier. By 1875 the meetings were augmented by Aberdeen Town and County Bank, The North of Scotland Banking Company, and The Caledonian Banking Company.

1875 saw a meeting of Bank Managers, on 1stFebruary, to consider a proposal from the Scottish Bankers' Literary Society to form a Bankers' Institute; the banks agreed that the proposal should be supported and that their employees "should be encouraged to avail themselves of it" (the Literary Society discussed such weighty matters as "Is the profession of banking favourable to intellectual culture?"!). The first appearance in the archival material of a formal document dated 26th June 1876 underpinned the meetings of bank managers for future decades - the "Agreements and Understanding amongst the Banks". In effect, this formidable document established a banking cartel which stifled competition. From now on, all the participating banks agreed to be bound by common regulations over a wide range of banking services, including: discount/interest rates, treatment of bills, clearing/endorsement/stamp duty and other aspects pertaining to cheques, various loan procedures, note exchanges, accounts of public bodies, etc. These "regulations" were augmented in due course by others and by comprehensive and specific tables of commissions and charges for every conceivable service/transaction. They were regularly reviewed, updated and frequently expanded; strict observance was expected, imposed and (usually) voluntarily observed.

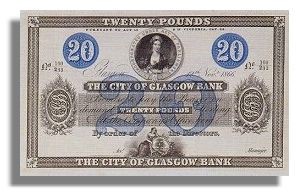

City of Glasgow Bank

However, 1878 saw an event that caused a reduction in the number of banks participating - more or less regularly - in the meetings of bank managers. At a meeting on 1stOctober that year, the (other) participants "noted that the affairs of the City of Glasgow Bank were in a much worse position than had been shown in the statements submitted by the authorities of the bank" and "resolved in the circumstances that no assistance should be given" (because no amount of assistance would "prevent a stoppage of the bank"). The bank closed its doors next day. The "line-up" now usually comprised: Bank of Scotland, The Royal Bank, The British Linen, Commercial, National, Union, Clydesdale, Town and County, North of Scotland, Caledonian Banking Co Ltd. (In 1885 Caledonian Bank, in dispute over the "agreed" deposit receipt rate, withdrew "from the concert which has hitherto guided the policy of all the banks in Scotland": the other banks subsequently changed their stance and Caledonian re-entered the fold in 1888.)

A rescue operation in 1890, led by the Bank of England and involving also the Scottish banks, conveys a sense of deja vu:

"It appears that the liabilities of the House amount to about £20,500,000 viz. £15,000,000 in the shape of acceptances and £5,500,000 in the shape of deposits. Owing to a large part of this amount having been locked-up in inconvertible securities, the House is unable to meet its obligations in the ordinary course, but the effect of a stoppage would be so disastrous that the Bank of England and many other banks and financial institutions in London had agreed to raise a Guarantee Fund with a view to prevent it."

The "House" in question was that of "Messrs Baring Brothers and Company, London", which got itself into similar difficulties a century later.

Frequency of Meetings

Returning to Scottish Affairs, we get an insight, in 1905, into the administration of the meetings and the considerable authority exercised by the Treasurer of the Bank of Scotland in his capacity as permanent Convenor, when the General Manager of the National Bank was constrained to write to him saying that he (the GM) "was inclined to think that the practical abandonment of reciprocal meetings (was) to be regretted". The Treasurer responded: "There has been no abandonment of meetings. I call them whenever the business seems to be of sufficient importance."(!) This did not satisfy the National Bank who pointed out: "There has been no meeting for nine months... I would very much like to ascertain how the other Managers regard the situation." The reply was short and to the point: "I have received your letter of yesterday, but as no good that I can see can result from this correspondence I must be excused from continuing it."(!) (National Bank persisted and a regime of quarterly meetings was eventually established.)

In 1907, the number of participants declined to eight following the acquisition by Bank of Scotland of Caledonian Bank and, about the same time, the merger of the North Bank of Scotland and the Town and County Bank in Aberdeen.

Chairmanship

Dissension again arose in 1920 when the British Linen proposed that Chairmanship of the meetings should rotate amongst all the banks. This attracted little support. The succeeding years, though interesting, were fairly uneventful from a structural point of view; numbers and modus operandi remained relatively unchanged until 1946 when there was a two-stage change in nomenclature from "Meeting of Bank Managers" to "Meeting of General Managers" to "The Committee of Scottish Bank General Managers". Developments then accelerated: 1949 saw the first reduction in numbers for four decades - from eight to seven - by the merging of the Clydesdale and North of Scotland Banks. 1953 saw a significant occurrence in the organisational structure of The Committee of Scottish Bank General Managers when a second, this time successful, attempt was made to wrest permanent chairmanship away from Bank of Scotland. The critical Minute is that of 12th January 1953 where it is recorded:

Convenor and Chairman

"The appointment of Mr Thomson (Royal) to be Chairman and Convenor of The Committee was proposed by Mr Brown (National) and seconded by Mr Campbell (Clydesdale & North).Mr Thomson's appointment, having been supported by Mr Anderson (BL) was carried.

Sir John Erskine (Commercial) intimated his dissent at this departure from practice and Mr Watson (Bank of Scotland) in intimating his regret at the decision, reserved the position of Bank of Scotland pending consultation with his Board.

Mr Thomson thereupon took the Chair.

A discussion took place as to the future arrangements for the conducting of the secretarial work of the Committee....."

However, that was not the end of the matter; controversy arose again when, in due course, Mr Thomson intimated his retiral from the Bank and, therefore, from Chairmanship of the Committee, whereupon Mr Campbell (Clydesdale and North) proposed, and Mr Brown (National Bank) seconded, that Mr Anderson (BL) be appointed Chairman. However, Mr MacDonald (Commercial Bank) submitted that "..as a matter of principle, the Chairman of the Committee should not be one whose bank is a subsidiary of an English Bank" because of the control which he alleged was exercised from London. Messrs Brown and Campbell took vigorous exception to what they saw as a slur on their "complete independence of judgement and decision." Mr MacDonald then moved the election of Mr Watson (Bank of Scotland); this was not seconded but Mr MacDonald persisted, by then proposing that Mr Thomson's successor in The Royal Bank be appointed.

"On a vote, Mr Anderson was elected Chairman." It all ended happily: "Mr MacDonald stated that his objection had been raised solely on grounds of principle and promised Mr Anderson his full support."

Future elections to the office of Chairman and, subsequently, to the office of Deputy Chairman, appear to have been uneventful and, more importantly, amicable.

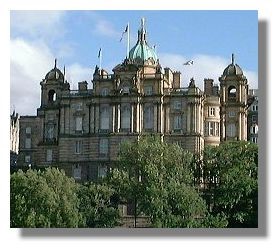

The Bank of Scotland's position as convenor and "leader" of meetings of the Committee (usurped in 1953) continued beyond that date in one notable area - that of the regular meetings with the Governor and Deputy Governor of the Bank of England. After a great "run for their money" - and giving great "value for money" - the "privilege" was amicably relinquished in 1999.

Creation of a Secretariat

Meantime, the "arrangements for the conducting of the secretarial work of The Committee" had culminated in 1953 in the appointment of Mr F.S. Taylor - in addition to his existing duties as (full-time) Secretary of The Institute of Bankers in Scotland. (The nomination was confirmed notwithstanding the Bank of Scotland view that the appointment of an independent Secretary was "inadvisable", while The Commercial Bank "Reserved the right to reconsider at any time (their) support of the new Secretariat"). Nevertheless, the Secretariat's workload increased steadily and in 1956 the Committee agreed "To attach a clerk from the Chairman's bank to assist with routine work..."; by 1959 Mr Taylor, whose duties with The Institute were also increasing, was constrained to give up the Committee work in order to devote all his attention to the Institute.

Mr Taylor's resignation led to the appointment that year of the Committee's first full-time Secretary - Mr James O Leslie (who resigned from Bank of Scotland to take up the post). The Secretariat, hitherto housed in the premises of the Institute, moved to its own office, made available by Bank of Scotland, at 101 George Street, Edinburgh.

Agendas continued to grow: the Minutes of the Meeting on 12th January 1965 extended to 23 pages, covering 38 items. As the "Agreements and Understandings" came to an end in 1965 the Committee effectively became a trade body whose role was to represent the collective interests of the banks. By this time, fortunately, Mr Leslie had acquired typing/clerical assistance and in 1971 an Assistant Secretary was appointed - Mr John C Sutherland (ex British Linen/Bank of Scotland). Mr Sutherland was later to become Secretary on Mr Leslie's retiral in 1974. The appointment of an Assistant Secretary became established as a permanent office and, by this time, the Secretariat was housed in Rutland Square, again sharing premises with the Institute.

Mr Sutherland, in turn, was succeeded in 1992 by Mr Alan Scott (TSB), who was followed in 1998 by Mr Gordon Fenton (The Royal Bank).

Merger activity between the Scottish and English banks in the early years of the 20th century rendered the need for the Committee less obvious, as the requirement for trade body involvement was increasingly met by the British Bankers Association in London. In 2003 it was decided that responsibility for running the CSCB should pass to the Chartered Institute of Bankers in Scotland. Consequently, Mr Fenton retired and Professor Charles Munn, Chief Executive of CIOBS, assumed responsibility for CSCB until his retiral in June 2007, when he was succeeded by Mr Simon Thompson. Mr Jim McGuigan, from the Institute staff, had responsibility for CSCB on a day-to-day basis until his retirement in 2013. Upon Mr McGuigan’ s retirement Mr Michael Downey, from the institute’s staff assumed responsibility for the day to day business.

The business of CSCB began to grow again, not least because the new Scottish Parliament began to introduce legislation that required input from the banks. Moreover, the Committee strengthened the level of its support and sponsorship of the work of the Scottish Business Crime Centre (SBCC) and continues to maintain representation on SBCC's board and on a number of sub-committees aimed at combatting and reducing various aspects of financial crime in Scotland.

The Secretariat is now accommodated at Drumsheugh Gardens, Edinburgh, in offices owned, and also occupied by, the Chartered Institute of Bankers in Scotland.

Bank Amalgamations

The Committee, by various amalgamations, was reduced in number from seven in 1949 to three in 1969 and, the following year, the current name - The Committee of Scottish Clearing Bankers - was adopted. The new name reflected the fact that the title General Manager was no longer common to all banks - Managing Director, Chief Executive and, of course, Treasurer all described the same level of seniority. Also, the "cartel" which had subsisted for almost a century and which, originally, had developed into the basis for the meetings came to an end in 1965. By this time, however, the Committee was established and recognised as the focal point of Scottish clearing banking. It was, in effect, the trade body for the Scottish Banks.

A beneficial spin-off from the enforced abandonment of the cartel was that it stemmed the decline in numbers by facilitating the entry in 1986 of TSB Scotland plc (later becoming Lloyds TSB Scotland) into the ranks of The Committee of Scottish Clearing Bankers to add another perspective to their collective wisdom and influence. That influence was by now making itself felt in London by individual bank representation on The Committee of London and Scottish Clearing Bankers; however, CLSB survived only until 1991 when it was absorbed into the British Bankers' Association.

The Committee Today

In June 2012 the Committee formally changed its name to "The Committee of Scottish Bankers" in order to accommodate a broadening of membership that would better reflect and represent the diversity of licensed deposit-taking institutions operating in Scotland.

Today, CSCB continues to act as a representative body of its members and to provide a forum through which its member organisations can discuss and debate matters of mutual interest or concern that are non-competitive in nature and that are of significant relevance to the operation of banking in Scotland. Regular contact is maintained with the Bank of England, the Scottish Government, financial regulators, relevant trade associations and professional bodies, economic development organisations and other key stakeholders. A dialogue is maintained with these bodies in order to provide advice, information and assistance and a channel of communication on matters significant to the operation of banking in Scotland.